This review does not contain spoilers until further down. Spoiler warning will be added before it.

Emotional books about grief and loss have been my jam lately

If you’ve been following along on my Instagram since I shared about my son Oliver’s stillbirth this past November, you know that I’ve been reading a lot of books related to grief and perinatal loss. Getting lost in emotional stories and learning about how others navigate grief has helped me process a lot of my own big feelings.

A Bookstagram friend who recently experienced a miscarriage first recommended Before I Let Go by Kennedy Rya to me, and it quickly started making the rounds on Bookstagram. I originally started reading it at the beginning of January but, chronic mood reader that I am, set it down after about 20 pages because it wasn’t the right vibe at the time. But I knew I’d come back to it soon, and I’m oh so glad that I did.

A second chance romance with themes of grief, loss, and mental health

This book was beautiful in so many ways. It meant so much to see myself represented in a woman of color whose baby was stillborn. It’s amazing that Kennedy Ryan broached the subject of stillbirth at all, let alone made it such a significant part of the plot.

Pregnancy loss, and especially late-term or neonatal losses, are traumas that are still horribly stigmatized in our society. Because of this, they are rarely represented or addressed in our media despite their prevalence (about 21,000 babies are stillborn in the US every year). I’m glad Ryan was willing to bring the topic to light, even though she herself has not experienced a stillbirth.

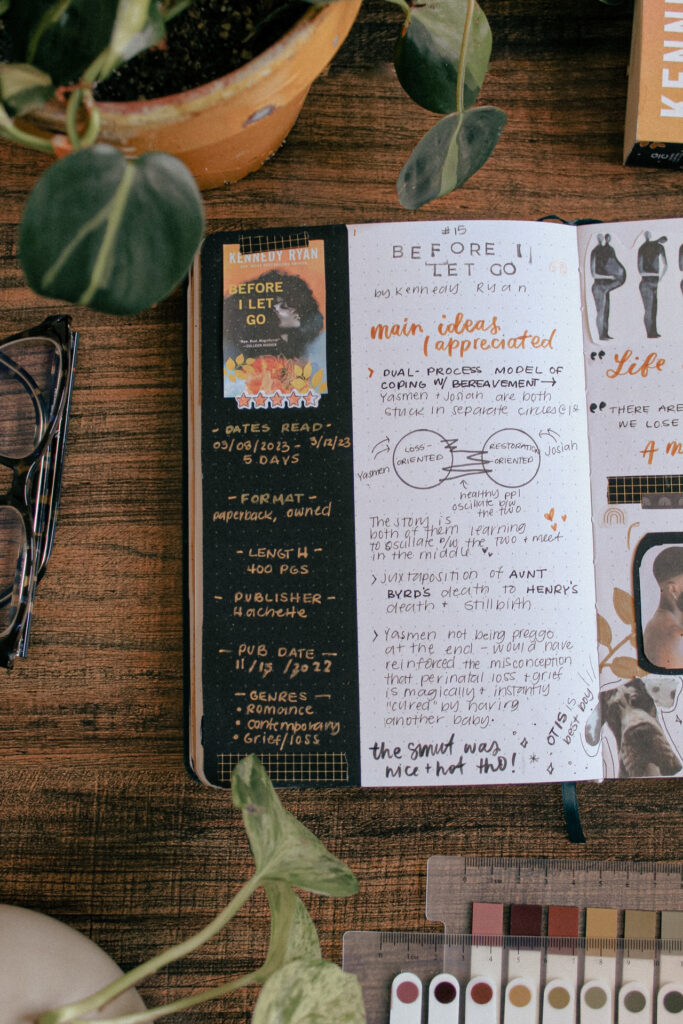

Although this is absolutely a romance (seriously, it has a One Bed trope), it could easily be classified as contemporary fiction because of the themes of grief, loss, and mental health struggles. Telling this story through the perspective of two parents who are both grieving differently is a brilliant way to frame this issue. They both experienced the same loss, but their ways of grieving couldn’t be more different.

Yasmen & Josiah each represent one side of The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement

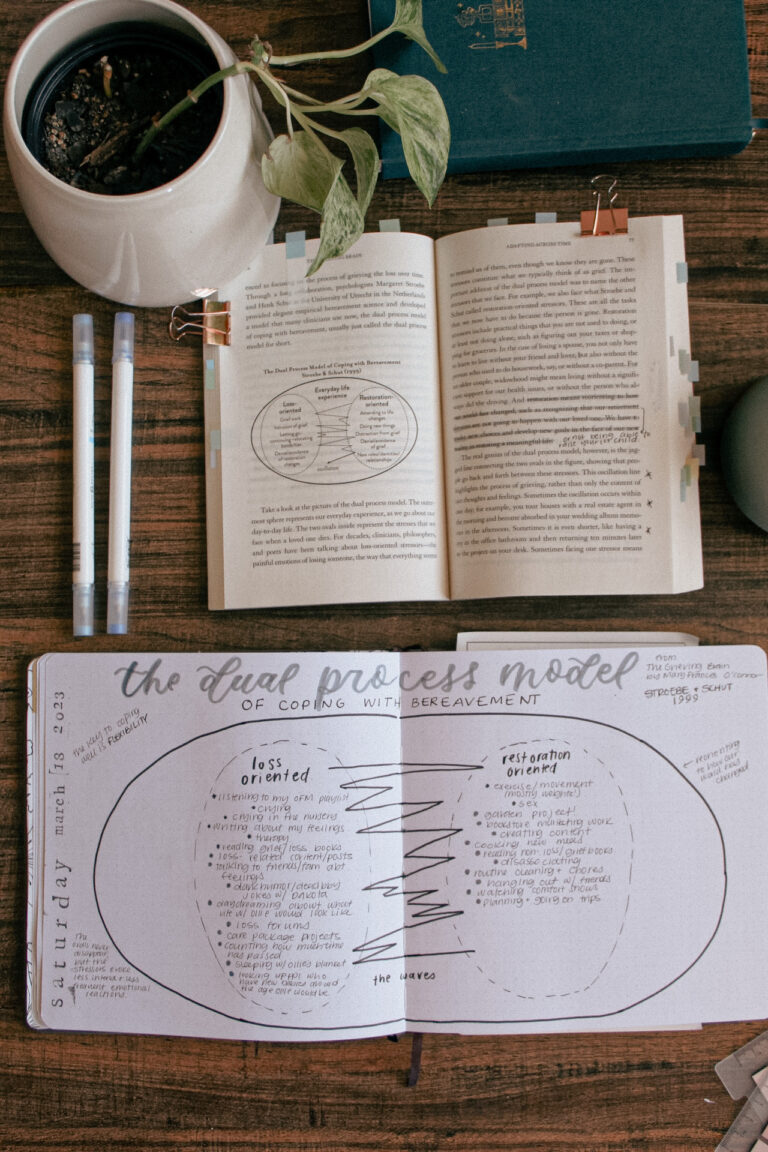

The Mood Reading Gods smiled down on me when they led me to read this book directly after finishing The Grieving Brain by Mary Frances O’Connor. One of the things that has stuck with me most from that book is The Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement, pictured below.

Explanation of the Dual Process Model

The model is an oval titled “Everyday Life Experiences” with two smaller circles within that oval. The left circle is titled “Loss-Oriented” and includes things like: grief work, intrusions of grief, denial/avoidance of restoration changes. The right circle is titled “Restoration-Oriented,” and includes things like attending to life changes, doing new things, distraction from grief, denial/avoidance of grief.

The most brilliant part of this model, however, is the jagged, asymmetrical line oscillating between the two. The waves of grief waxing and waning with no discernible pattern.

Yasmen and Josiah’s characters perfectly represent each of these smaller circles with how they grieve. Yasmen stays firmly lodged in the “Loss-Oriented” bubble for a while: she cries in the nursery often and is so caught up in her emotions that she can barely function. On the opposite end, Josiah doesn’t stray from the “Restoration-Oriented” circle: he works constantly, distracts himself from his pain and avoids his emotions as much as possible.

The disconnection that stems from grieving in different ways

But for Yasmen and Josiah, and for many couples who have experienced loss together, disconnection happens because each is stuck in their own bubble on opposite ends of the spectrum. They are so preoccupied with trying to survive the crippling pain of child loss that neither has the energy or resources to meet in the middle.

While you’re in the throes of deep grief following a death, our own emotions often feel too enormous for us to manage. How can we help someone else when we barely understand our own emotions?

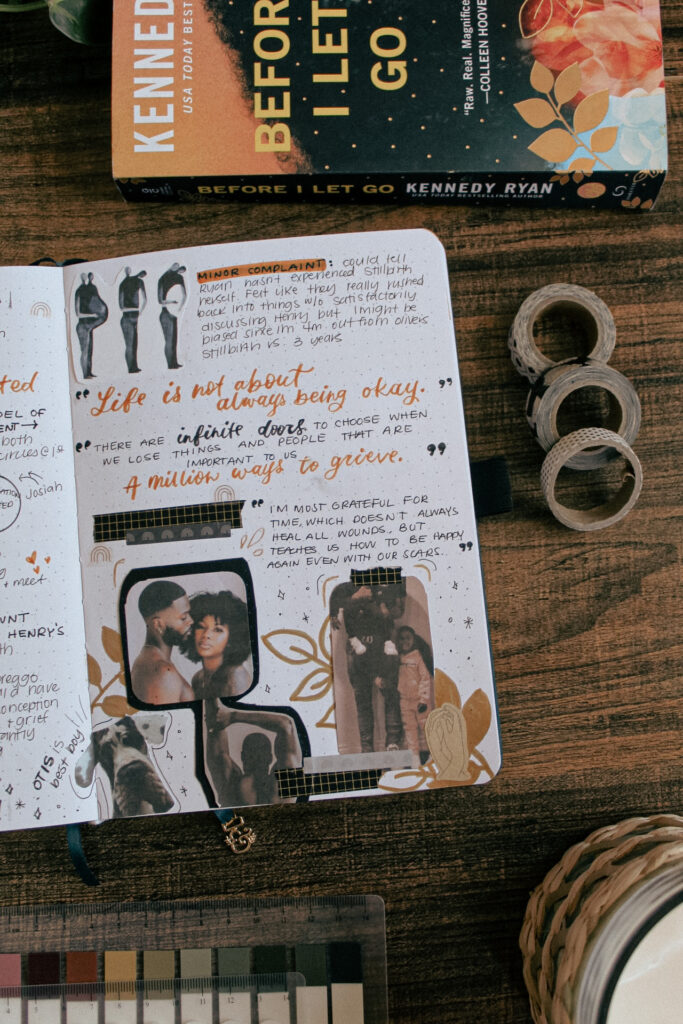

As Josiah’s therapist wisely states, “There are infinite doors to choose when we lose things and people that are important to us. A million ways to grieve (pg 114).” However, those who are resilient in grief will oscillate between the two states to some degree. The balance is rarely an even split, especially not at first, but there is a healthy push and pull between being present with your emotions and redirecting your focus.

The heart and soul of this story is about each of them finding this balance within themselves, and finding their way back to each other along the way.

The juxtaposition of perinatal loss and traditional death

I also appreciated that, in addition to Henry’s stillbirth, the couple was also dealing with the loss of Josiah’s Aunt Byrd, a mother figure to both him and Yasmen. The comparison of the two losses helps highlight why perinatal loss is such a unique form of grief.

Both Josiah and Yasmen, as well as many other characters, have several distinct memories of Byrd they can recall when they miss her. They can talk to others about Byrd and reminisce on fond memories. Yasmen bakes some dishes from Byrd’s recipe book, a little ritual to mourn her. At one point, after Josiah tastes one of the Byrd recipes that Yasmen recreated, he starts thinking about “all kinds of things Byrd left for me to remember her by (pg 201).”

But they have no rituals for Henry. They have few, if any, physical items to remember him by. They can’t really share memories of him with anyone else other than each other, or maybe their other kids.

Grief is difficult to handle no matter the circumstances, but to lose a soul who has not yet or just recently entered this Earth is isolating in a way few other losses are.

SPOILER ALERT GOING FORWARD!

A rainbow baby doesn't magically remedy the pain of pregnancy or infant loss

I am so, so relieved that the book didn’t end with Yasmen being pregnant. I didn’t think too hard about this until I talked to another loss mom, Cori, who had also just finished it. We both agreed that Yasmen being pregnant at the end would reinforce the misconception that having another baby after a loss fixes everything, and “cures” the grief.

I think Emma Hansen says it best in her memoir Still about her son Reid’s stillbirth, as she’s discussing the term rainbow baby:

“The meaning behind the term is an attractive one, because don’t we all want to believe that even when awful things happen, happy endings are within reach? That rainbows exist? They do; I have seen them, lived inside of them. That usual definition also makes me feel uncomfortable. Because it feeds into what we so wrongly perceive about grief: that there is an end to it. If the grief from Reid’s loss is a storm and if that storm ended to make way for this rainbow, doesn’t that imply that the pain of losing him ended too? Wouldn’t that mean that the love that made that grief possible was gone?

Emma Hansen

Pregnancy after loss is a whole other beast with its own struggles. Ending with Yasmen being pregnant without delving into those struggles would feel too much like a nice, pretty, neat bow tied together in a satisfying way. But that’s just not the reality when it comes to child loss.

What else Kennedy Ryan nails about life after loss

There are a few passing scenes in this book that were so realistic. At one point near the beginning, Yasmen has a conversation with an acquaintance who shares about her own pregnancy losses. This happens so often – once you experience this type of loss, the floodgates open and you’re bombarded with stories of others’ losses. It’s like there’s this invisible world full of bereaved parents all around you that is fully unveiled when your own child dies.

The other scene that stood out was when Josiah runs into his neighbors who recently adopted an infant. Josiah mentions how uneasy he has been around infants since Henry’s stillbirth. I appreciate that Ryan included this interaction because it really does suck sometimes to be around happy, healthy and alive babies after your own dies. It is a very common grievance among recently bereaved parents.

Two people missing, not one

I did have a few issues with the story. There are few times when it is glaringly obvious that Ryan has never experienced a stillbirth herself. Which is okay; if people only wrote about things they’d experienced, literature would become pretty boring. But it can lead to misrepresentation sometimes.

The scene where this is most obvious occurs shortly after Yasmen and Deja reconcile. It’s a snow day, and Yasmen, Deja, and Kassim are all snuggled up in bed together watching television. Yasmen is content and thinks “Tucked beneath this duvet, inside this bed, is my whole world. These are the people who matter most. Only one is missing.”

When I first read that last sentence, I assumed she was referring to Josiah. But a loss mom would never forget that their dead child was also missing as well. If this is meant to refer to Henry, then it seems weird that she would leave Josiah out at that point in the story.

No discussion of ways to memorialize Henry

I also felt like Yasmen and Josiah’s official reconciliation was a bit rushed. There wasn’t quite enough talk and discussion of their feelings about Henry for my liking before they decided to move back in together. I think it would have been beautiful if they had developed a way to formally honor Henry’s memory together as a family unit moving forward.

I think someone who directly experienced that type of loss would have included something like that as part of their reconciliation process. Formally honoring his place in the family could be a way for them all to continue healing individually and together.

Overall, it was truly a remarkable story that I will probably be recommending to people forever. I think that even those who haven’t experienced perinatal loss will at the very least appreciate the way emotions, mental health, and therapy are discussed. We need more fiction books that deal with grief and/or perinatal loss, and I’m so grateful that Ryan wrote this story. I am really looking forward to a sequel!

Just for fun, here’s the mood board I created based on this book.

If you’ve read this book, leave a comment with your thoughts. I would really love to discuss this book with others.

This blog post contains affiliate links.