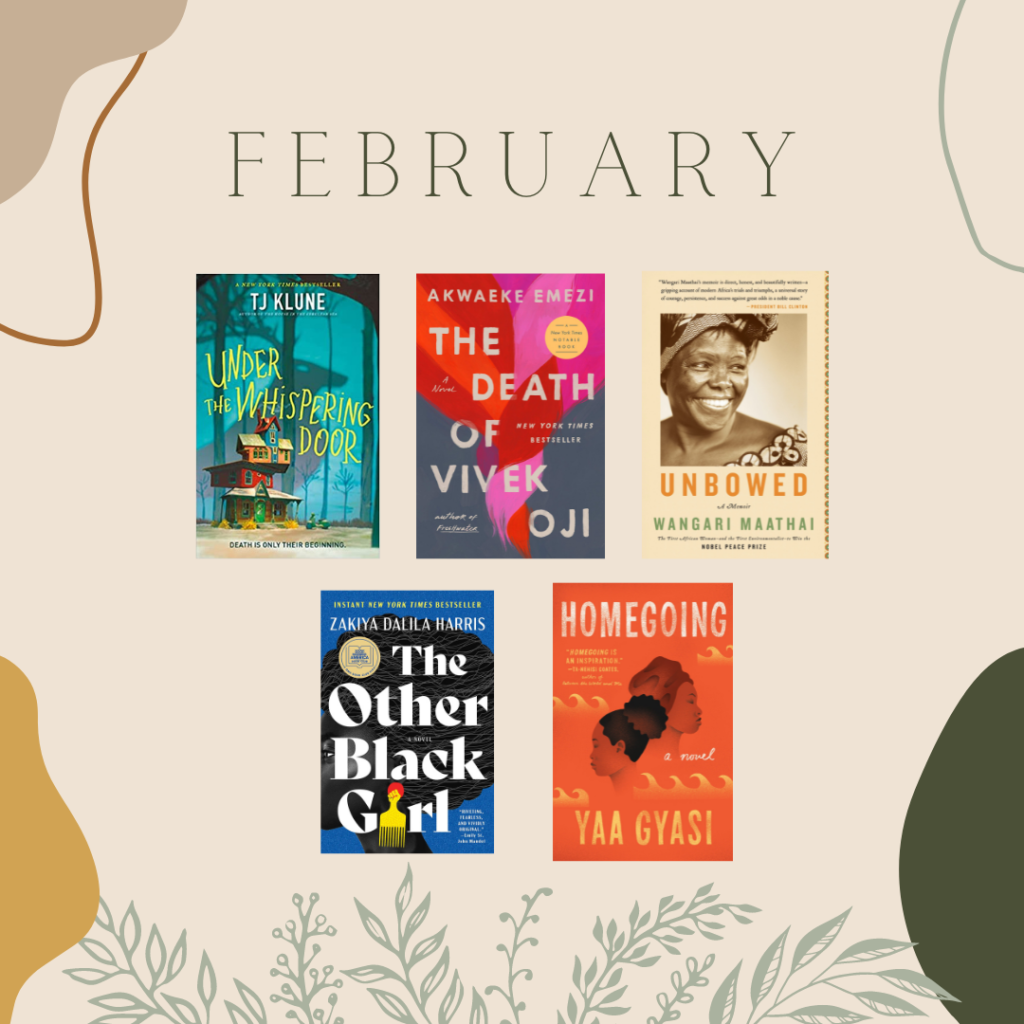

While every month is a great month to consume work by BIPOC, I do love to hone in on literature by Black authors in February for Black History Month. I especially wanted to focus on stories by African authors that take place in Africa. My father is from Kenya, and although I’m unfortunately not very knowledgeable or in-tune with my African heritage, I felt a deep desire this month to further engage with these cultures. So after I finished the T.J. Klune audiobook I started in January, I dove into some of my TBRs for the month.

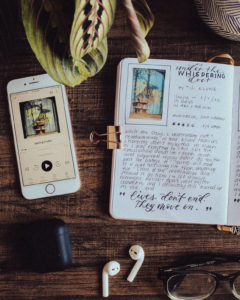

#6. Under the Whispering Door by T.J. Klune

Goodreads | Storygraph | Amazon | ThriftBooks | Bookshop | Author Website

TW: suicide, death, loss of a loved one

This is an undeniably cute story, and fans of The House in the Cerulean Sea will certainly appreciate it. However, for such deep themes as death, grief, afterlife, suicide, and friendship, the overall story fell a little flat to me. This story felt like the embodiment of the “live, laugh, love” platitude minus the cringe aspect. As an adult who has experienced the death of a loved one, I don’t feel like this particular novel provided any new insights into the subject that I haven’t heard or read or seen several times over.

The strong point of this book definitely lay in its characters. Klune is adept at creating and developing unique and loveable characters. He certainly does have a thing for loner, bureaucratic protagonists who blossom into their full, queer, unregimented selves via the power of true friendship and love.

However, unlike in Cerulean Sea, the primary romantic relationship in this book felt underdeveloped and rushed to me. I think that the story would have been stronger if said relationship had remained platonic, but I also understand that coming to terms with and embracing his bi-sexuality was part of Wallace’s arc. Also, yay for bi-sexual protagonists! As a bi-sexual individual myself, I appreciate Klune highlighting Wallace’s bi-sexuality instead of making him a once-closeted homosexual, as is often the case for queer characters.

I listened to this book an audio, and I think the narrator, Kurt Graves, did an exquisite job at capturing the self-righteous and indignant tone of Wallace; he gradually and skillfully encompasses a lighter timbre as Wallace’s heart unfolds before his new companions.

All in all, it was an entertaining read. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it to others, but I certainly don’t regret reading it. I’m anxious to see what Klune writes next.

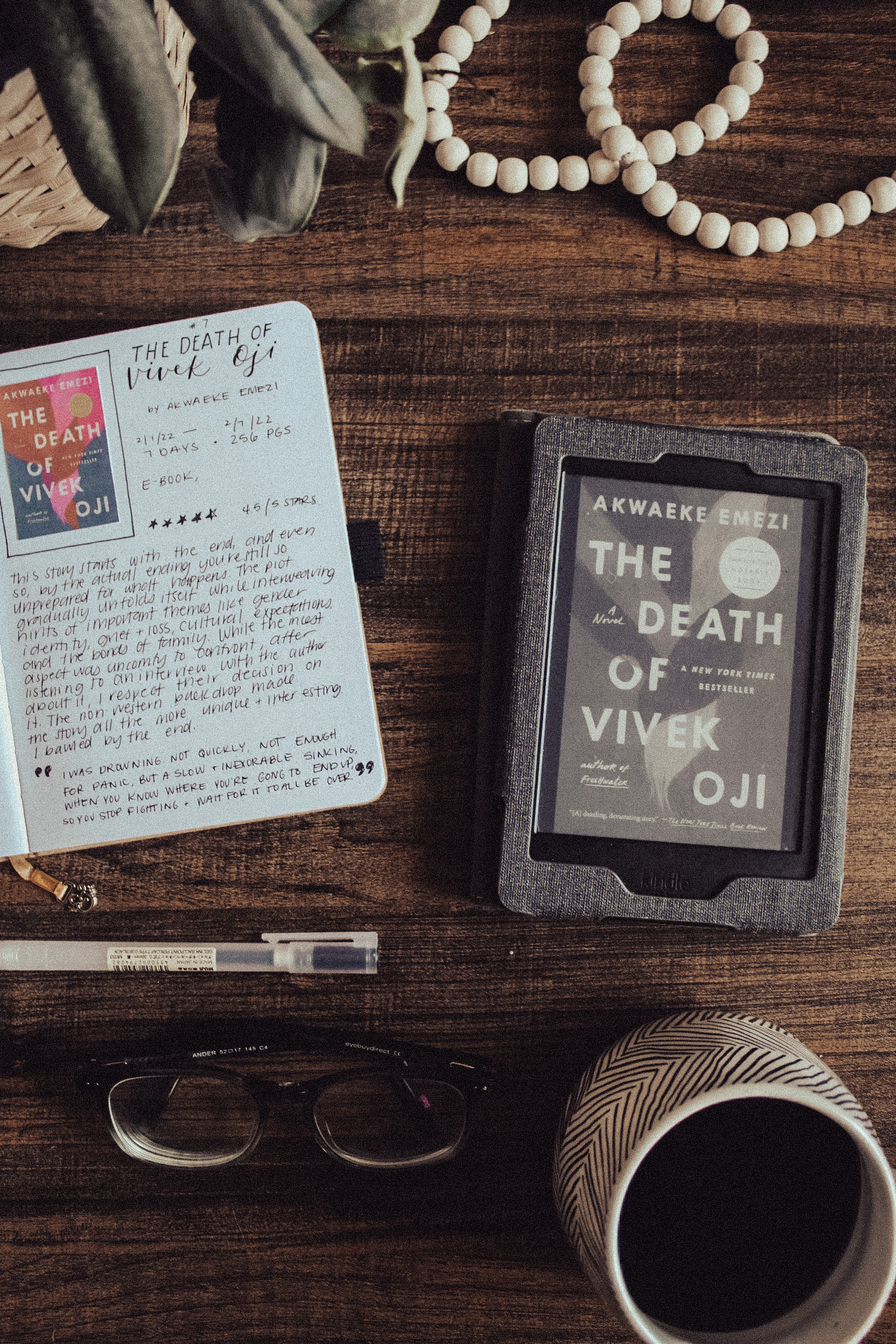

#7. The Death of Vivek Oji by Awkaeke Emezi

Goodreads | Storygraph | Amazon | ThriftBooks | Bookshop | Author Website

TW: incest

You’d think that the inherent spoiler in the title, and the “starting with the end” narration style would prepare you emotionally for this book, but trust me when I tell you it doesn’t. The story of Vivek Oji’s tragic and untimely death and the events that led up to it gradually unfolds itself, interweaving themes of gender identity, shame, grief and loss, cultural expectations, and family bonds throughout.

The non-western setting of this novel sets it apart form its peers, reinforcing just how permeating some of our social constructs of gender are, across cultures, language, and borders. The dialogue, while mostly in English, is intermixed with phrases of Igbo, and certain unorthodox grammatical choices even while speaking English reinforce that this is not a native tongue for these characters.

One aspect I found particularly intriguing was the shift from first person to third person narration depending on the character and the scene. The two main characters, Vivek & Osita, are the only characters whose perspective is narrated in first person. Even then, some of their story is narrated in third person. These narration choices reinforce the juxtaposition of how these characters feel inside and view themselves vs. how others see them and expect them to behave, which is a central theme in this book.

While there was one tangential and minor plot point that I didn’t quite understand the context or importance of, I was captivated by this story from start to finish, despite having a vague idea of how the plot would progress. This was my first introduction to the Emezi’s writing, and I’ll be surprised if it doesn’t end up in my top 5 for fiction by the end of the year. I’m excited to read more of Emezi’s work, and see what they publish next.

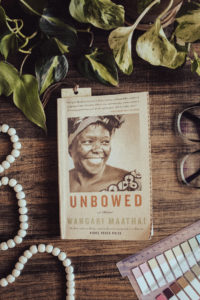

#8. Unbowed by Wangari Maathai

Goodreads | Storygraph | Amazon | ThriftBooks | Bookshop | Author Website

Wangar Maathaii is a woman who was born decades before her time. While she is most well-know for her environmental work with the Green Belt Movement and her years serving in the Kenyan Parliament, the efforts of her activism extend far throughout Kenya and beyond.

Maathai received her doctorate degree (one of the first women in Africa to do so) at a time when her country was recovering from the effects of colonialism. Her education and time abroad in America allowed her to witness firsthand just how many issues (sexism, corruption, land destruction, climate change, poverty) plagued her country. She understood the intersectionality of these many issues YEARS before the term was officially coined.

And this understanding fueled fierce and unending action. You could fill an entire trash bag of scrabble blocks with just the acronyms of the many organizations and committees she founded, co-founded, or chaired. She wrote letters to the establishment, called out the government via the press, attended numerous protests, educated the masses through grassroots efforts, and was jailed several times as a result of her sheer persistence. The massive number of obstacles Wangari faced without being even slightly deterred is truly impressive.

One of my favorite aspects of this book is that, alongside her personal story, Maathai provides a succinct history of Kenya from the mid-20th century to early 21st century. Born into a colonized Kenya, Maathai brushes up directly against the many issues plaguing the country as she matures. It is a coming of age story for Kenya as much as it is for Maathai, and she is instrumental in progressing the country through its many growing pains.

This memoir was particularly special to me because I am half-Kenyan. I loved learning about the history of my father’s homeland through Maathai’s story. She is also part of the Kikuyu tribe, same as my family, and it was enlightening to explore the many different cultures, ethnicities, languages, and customs that comprised newly independent Kenya. The fact that she spent 4 years in Kansas, where I was born and raised, just made this story all the more poignant to me. It’s honestly one of the most inspirational memoirs I have read to date.

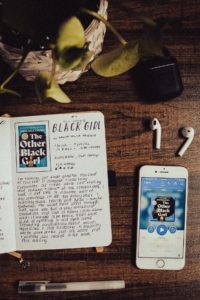

#9. The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris

Goodreads | Storygraph | Amazon | ThriftBooks | Bookshop | Author Website

I think this is the longest it’s ever taken me to listen to an audiobook, partially because the plot never gripped me. The primary emotion I felt when I finally finished it was relief that it was over. While it undoubtedly opens some necessary albeit difficult conversations about mico-aggressions in workspaces and the practice of code-switching, the book as a whole was fairly disappointing.

The first 3/4ths of the book are severely overwritten, with a few too many POVs that I didn’t feel were necessary to the story-telling. The majority of the plot is crammed into the last 10% of the book, and the “reveal” at the end was almost comical.

Nella wasn’t an endearing main character. It felt like she had no identity outside of being a black woman. Nearly every thought she thinks or action she takes inevitably leads back to her blackness and/or womanhood somehow. She has no hobbies outside of what is required of being a black woman working at a publishing house. By the end of the story, this narrow-mindedness of Nella’s is revealed to be somewhat intentional; however, I still didn’t feel her traits were fully reconciled once I finished.

Many of Nella’s ideas and opinions about what it means to be Black in America were veering on offensive. This subject was particularly touchy for me, so I fully acknowledge that this particular opinion originates in many personal biases. As a half-black African-American who grew up almost exclusively around white communities, I have always struggled with the concept of being “Black enough,” and a lot of Nella’s inner-musings seemed to reinforce a lot of generalizations about Black Americans.

It has taken me many years of reflection and self-examination to fully internalize that BIPOC are as varied and unique as people with whiter skin; to understand that, while Black cultures To assume that another is internally similar to you simply because you have similar skin tones, as Nella originally assumes about Hazel, can, in my opinion, sometimes reinforce harmful generalizations about Black folk. This may be a controversial opinion, so if you have read this book and disagree/agree, please let me know! Let’s talk about it.

The audiobook narrators were good with the material, but even the best narrator in the world wouldn’t be able to salvage this book. I’m hoping Harris’ next story is more concise and cohesive.

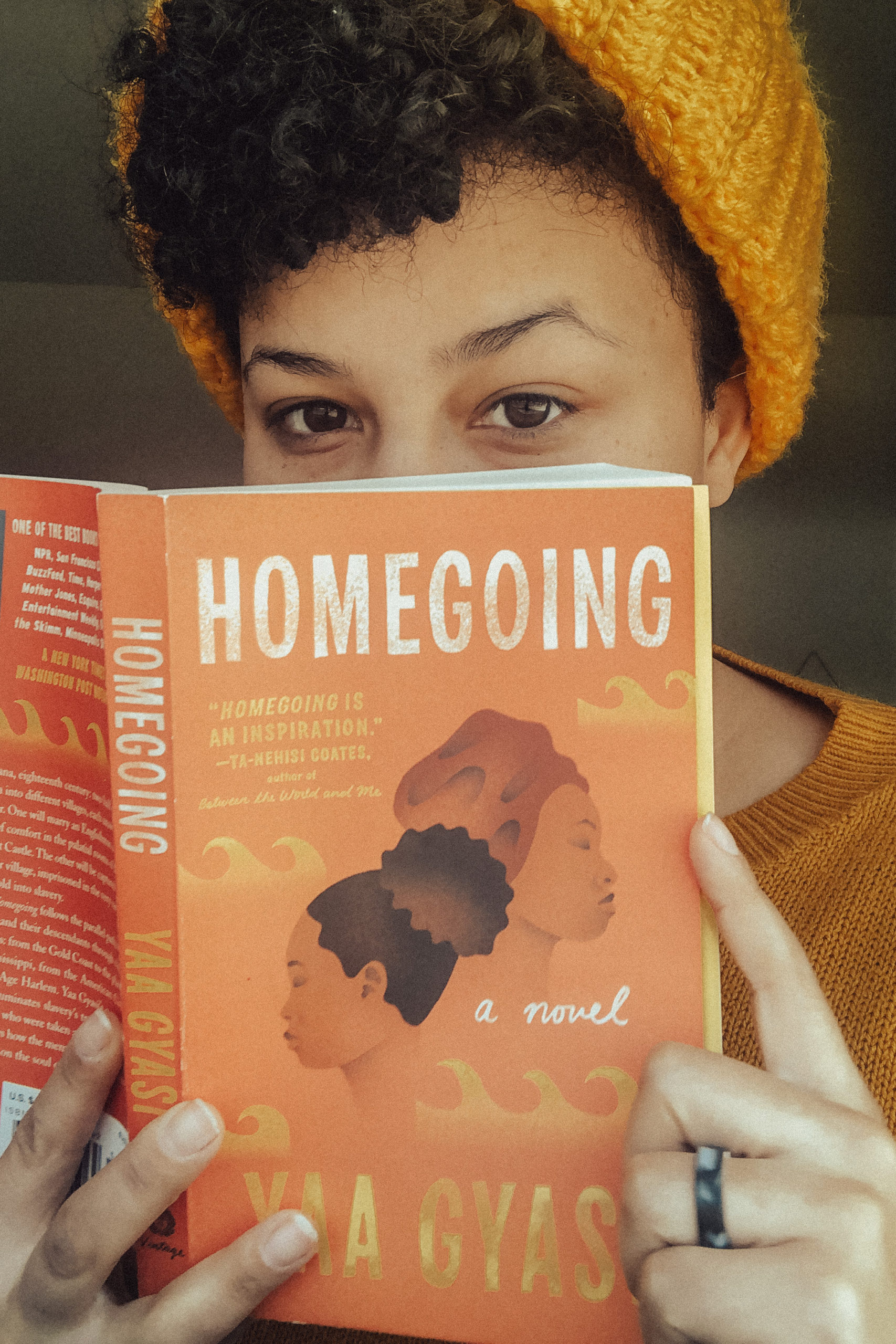

#10. Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Goodreads | Storygraph | Amazon | ThriftBooks | Bookshop | Author Website

If you’ve followed me for a bit, then you likely will have seen me post about Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi at least once. It was my #1 favorite read of 2021, and instantly became one my favorite books of all time. I was so excited to read this one ever since buying it in early January, and the number of people who told me how good it was only added to the hype.

Let me tell you: the hype DID NOT DISAPPOINT! At all. Spanning 300 years and 8 generations of a single family, Homegoing is truly a masterpiece, and may well be the crowning jewel of multi-generational historical fiction. It also tied so well into the African literature I selected for this month, as it further details the horrors and struggles brought by British Colonialism in Africa and how it directly correlates with the legacy of slavery and racism in America.

There are two things that set this story apart from other historical fiction: First is the short “snapshot” into each character’s life we receive, rather than following them in more detail from birth to death. Each character has only a single chapter dedicated solely to them, although you may catch glimpses of some characters in the chapters of their descendants. However, due to Gyaasi’s masterful writing, each chapter and the story as a whole felt like exactly the right length.

The second is the way Effia and Esi’s descendants mirror and conflict with one another as each line deals with the horrible effects of slavery in both America and Africa. Gyaasi crafts a narrative that intricately showcases the generational trauma and institutional racism that snowballed from the colonization of African nations, and that many Black individuals still feel experience today to varying degrees.

I feel pretty confident that this will also end up in my top 5 favorite fiction reads for the year, and I’m officially an auto-buy fan of Gyasi. I cannot wait to see what she writes next!

Pingback: 2021 Favorite Books and Reading Statistics - Planned & Planted